(Infinity and Beyond is a bi-weekly series in which Josh Spiegel looks back at the history and making of every feature film in Pixar’s filmography. In today’s inaugural edition, he kicks off the column with the movie that started it all: 1995’s Toy Story.)

There are only a handful of films released in the first century of cinema that can be categorized as truly influential to more than just a few young would-be filmmakers and/or critics. Films such as Birth of a Nation, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and Citizen Kane are valuable cinematic items not because of their quality (though the latter two are quite incredible), but because they paved a path for the future of their respective mediums. The films we love now literally could not exist without these titles paving the path for the future.

One film that can be safely deemed influential for representing a sea change in the art of animation and the craft of cinema is the 1995 adventure comedy Toy Story. And Pixar Animation Studios, the group that produced and animated the film in the San Francisco area, is now one of the most powerful and dominant forces in all of Hollywood. For a lengthy time, its creative leader wasn’t just overseeing Pixar, but also Walt Disney Animation Studios and Walt Disney Imagineering. Though John Lasseter departed the company in acrimony in 2018, Pixar’s overall legacy is unblemished.

2020 marks the 25th anniversary of Toy Story, and thus the quarter-century anniversary of computer animation being seen as a viable, and now essentially required, way to make animated features for the whole family. Just as I explored the films of the Disney Renaissance at /Film in 2019, I’m fortunate enough to be doing the same for the entire filmography of Pixar Animation Studios this year with Infinity and Beyond, culminating with discussions of the company’s one-two punch in 2020 of Onward and Soul. For now, though, let’s start with the humble beginnings of a studio that fought to prove the value of computer animation before becoming its standard bearer.

That’s Not Flying

When people outside of Hollywood hear about reshoots on a given live-action project, they may presume the worst. If a live-action film has to go through millions of dollars’ worth of rewrites and reshoots, it’s often a sign that the story is not in a good place. Of course, reshoots don’t guarantee a film’s success or failure with critics or audiences. Look at the two Star Wars Story titles of recent years, Rogue One and Solo. Both went through extensive reshoots, the latter even replacing its directors mid-production. One of them made a billion dollars worldwide. The other one is Solo.

Though the whiff of trouble can be true in live-action, and can turn off audiences, it’s not quite as simple in the world of animation. Rewriting storylines, dialogue, and character details are the name of the game, and the existence of such revisions rarely implies a film’s eventual success or failure.

Yet the specter of failure because of studio demands couldn’t be far removed from the minds of the Pixar staff who were sitting in a conference room with Disney executives in the fall of 1993. Pixar, led by co-writer and director John Lasseter, had just presented story reels for what would become the first fully-computer-animated feature film. To say that the presentation went poorly is an understatement. In Pixar lore, as discussed in David Price’s invaluable studio biography The Pixar Touch, the meeting, taking place on November 19, 1993, was known as the “Black Friday Incident.”

The film everyone knows and loves wasn’t present on that day, even though the story reels featured dialogue performed by Tom Hanks and Tim Allen. Their characters, the neurotic Sheriff Woody and the arrogantly heroic space ranger Buzz Lightyear, had an unpleasant chemistry at the time. What should have been jocular sounded mean-spirited. For a comedy, it didn’t seem to be that funny. Instead of wit, there was noxious sarcasm.

Lasseter and the team were given three months by the Disney leadership to fix what seemed like an unfixable problem. Whatever else was true, Pixar could only shoulder some of the blame for the largely unfunny story reels they’d presented to Disney. According to Walter Isaacson’s biography of the late technological pioneer and Pixar chairman Steve Jobs, Jeffrey Katzenberg asked Disney executive Thomas Schumacher why the reels were so bad. Schumacher’s answer was simple: “Because it’s not their movie anymore. It’s completely not the movie John set out to make.”

T-O-Y, Toy

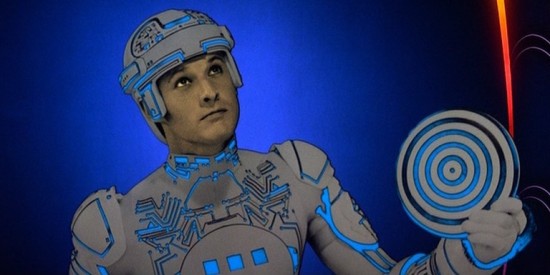

John Lasseter had envisioned a computer-animated feature well over a decade before the Black Friday Incident. In the early 1980s, Lasseter was working at Walt Disney Feature Animation, during a period of time not well-known now for its strong feature output. (One of the projects on which Lasseter is credited is the holiday short film Mickey’s Christmas Carol from 1983.) But one of the major technological breakthroughs of the era is a film Disney released in its attempts to capitalize on the widespread success of Star Wars. For years, the 1982 film Tron was well-known as an expensive sci-fi adventure that failed to capture as many hearts and minds at the box office. (And for fans of The Simpsons, it might have been best known as the subject of a joke in a mid-1990s “Treehouse of Horror” episode.)

Tron, though, was proof of the viability of computer animation and computer-generated imagery in a major mainstream film. Lasseter didn’t work on the project, but when he saw footage of the light-cycle scene from the film, he instantly understood the possibilities that opened up from its very existence. He wasn’t content to wait around, either — he pitched Disney’s executives at the time on a computer-animated film based on The Brave Little Toaster, in which inanimate objects with human personalities go on an adventure in the hopes of returning to their friendly owner, a loving little boy.

The pitch went about as badly as could be expected: Disney rejected it, and soon Lasseter himself, firing him. (The Brave Little Toaster was eventually made as a largely hand-drawn animated film, released in 1987 to a few theaters and eventually gaining a cult fanbase.) Lasseter became a part of Lucasfilm in its post-Return of the Jedi era, specifically working on a subsection of George Lucas’s company, the Pixar Image Computer. In the earliest days of Pixar, what Lasseter was doing was less its leading principle and more a way to demonstrate the power of the computer technology Lucasfilm owned. Making computer-animated short films was, in the mid-1980s, just a nice way to convince larger companies that the technology had legs. (Then, as now, there wasn’t a lot of money to profit from in making short animated projects.) But once Steve Jobs bought Pixar, Lasseter’s work kept coming and gradually gained Pixar a good reputation, with the 1988 short Tin Toy winning the Oscar.

Continue Reading Toy Story Revisited >>

The post 25 Years Ago, Pixar’s ‘Toy Story’ Changed Animation Forever appeared first on /Film.